Case-control studies can’t calculate incidence because the diseased subjects and healthy controls start with a similar baseline. This makes it impossible to calculate relative risk. However, this method is very efficient, and an odds ratio of 6.56 is a close approximation to risk ratio. Case-control studies are useful when a condition is rare or an outcome is not frequent. However, case-control studies have some problems.

Problems with case-control studies

While case-control studies are effective at providing early clues and informing future research, they are less reliable than planned studies. A planned study records data in the present, while case-control studies study events that occurred years ago. The data from a case-control study is skewed due to recall bias. Furthermore, people may recall certain exposures that did not occur in the past without even knowing they were involved in the risk factor. Also, these people may be making subjective connections between the exposures they reported.

One of the biggest problems with case-control studies to calculate incidence is the selection of the controls. In order to be reliable, the controls should be representative of the population at risk for developing the disease in the first place, and they should also have the same levels of exposure as the cases. This can be challenging in practice, but in the end, the case-control study remains the gold standard for many epidemiological studies.

Another issue with case-control studies is their limited power to measure causality. The methods employed are not as precise as randomized controlled trials and cannot prove causality. Furthermore, they do not require a large number of participants, which makes them more efficient. As these studies are observational in nature, they may not pose any ethical issues. In addition, case-control studies may be biased by the presence of confounders such as socioeconomic status or other factors.

While case-control studies can be used to establish an association between an exposure and an event, it cannot prove causation. In case-control studies, the investigators may include unequal numbers of controls and cases, thus increasing the study’s power. Therefore, it is important to know what the study is really investigating and how it compares to other similar cases. But the problems with case-control studies to calculate incidence are still significant.

Another common problem is selection bias. Hospitalised patients are often used as controls, but this may understate the strength of the association between exposure and outcome. A better alternative is to recruit community controls. Community controls should be of a similar risk as hospitalised patients. Researchers often enrol more than one control group in case-control studies. But in general, this method is not more effective. So, what are the problems with case-control studies?

The main problem with case-control studies is that the risk ratios produced are inaccurate. The researchers cannot assess potential risk factors from the equalized matching variables. As a result, the results of the case-control studies are rarely informative in determining the incidence of the disease. In this case, the researchers are left with odds ratios for each risk factor. The results of these studies are interpreted in a different way from those obtained with a cross-sectional study.

Reliability of case-control studies

The method of calculating incidence from case-control studies has its limits. This type of study has limited power because it cannot confirm different levels of disease or types of disease in a population. Moreover, cases are defined as those who had a disease or were free of it. However, this is not a major problem, as it is possible to collect a sample of cases and a control group from electoral rolls or population registers.

Case-control studies have several benefits over prospective studies. For one thing, they do not require the participation of large numbers of people, and thus can evaluate multiple risk factors and only need a small group of participants. Moreover, they can devote limited resources to analyze fewer people, and they pose no ethical dilemmas. Another benefit of a case-control study is that it is observational and involves people who have experienced a condition. As a result, it requires less time to conduct, since a disease or condition has already occurred.

Case-control studies also face bias. While they are useful for early clues and inform further research, they are not as reliable as planned studies. While planned studies record data in real time, case-control studies analyze data collected several years ago. Recall of exposure information from the past is often unreliable. Furthermore, people may make subjective associations, which may not be true. As a result, it is difficult to estimate the actual incidence of a disease from case-control studies.

Another benefit of case-control studies is that they can be matched to controls on various factors. This increases statistical power and precision of results. In case-control studies, there are often three or four controls for every case. In addition, case-control studies are cheaper than other studies and allow researchers to study rare diseases and multiple exposures. There are other advantages as well. A case-control study is also less subjective than a population-wide survey.

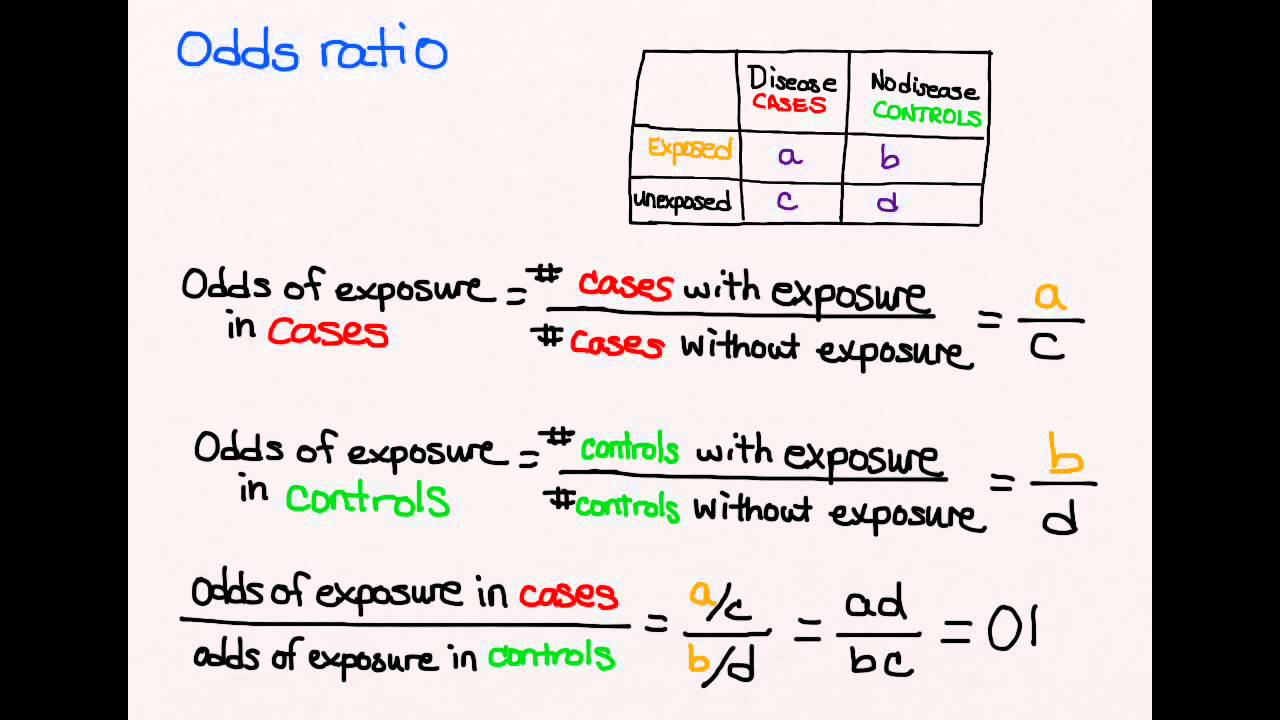

In case-control studies, the data are usually set in a two-by-two or four-fold table. This is in contrast to cohort studies, which have the entire study population as the denominator. The case-control study results are best expressed as odds ratios, which are the ratio of exposed to non-exposed individuals in the case group. This measurement is closer to the relative risk than the former method.

When the incidence is calculated, it is important to evaluate the reliability of the data obtained. If the study is inaccurate or lacking in data, the results may be inaccurate. For example, the odds ratio is not reliable when the data used are not sourced from the same population. Likewise, the odds ratios of case-control studies do not correspond to the real incidence rates. A case-control study is more likely to show a correlation between the exposure and the outcome.

Cost effectiveness

A cost-effectiveness analysis is a systematic method for comparing health interventions based on their costs and outcomes. It is the process of estimating how much a particular intervention costs for each unit of health outcome gained or prevented. Cost-effectiveness is a crucial part of any health research project, and is increasingly used to help policy makers make informed decisions about health care investments. In case control studies, the costs are typically measured as a percentage of total health care costs or the number of lives saved or improved.

When performing case-control studies, a high-quality estimate of incidence is important to guide decision-making. Incidence is the number of cases diagnosed in a population and the number of controls. Incident cases are more informative than retrospective cases because they are more likely to recall past exposures. Furthermore, incident cases can be more readily identified in the temporal sequence of the disease’s development. Incidence density studies can be very accurate and can help researchers make informed decisions about treatment and prevention strategies.

When calculating the cost-effectiveness of a treatment, a patient-level study of the incidence of a disease is the most accurate way to calculate the cost-effectiveness ratio of a specific intervention. The higher the incidence, the lower the cost-effectiveness ratio. This is the same for randomization studies. When calculating incidence in a case control study, one must consider the randomization of the groups. If a randomization strategy is used, it can be quite misleading.

When comparing the cost-effectiveness of a malaria treatment, one needs to consider the implication of the IRS on the study’s outcomes. Targeted IRS would be more cost-effective for the public health sector at a lower case fatality rate because fewer cases mean fewer deaths or DALYs. But it is important to note that in this study, the incidence varied greatly between the years. The second year in South Africa, for example, increased dramatically.

The cost-effectiveness of an intensive cardiovascular control strategy would cost an average of $28,000 per QALY gained. At $50,000 per QALY, the probability of intensive control rose to 79%. The ICER for a $100,000 intervention would be $93.

Using the case-control approach is highly effective for studies with long latency periods and rare diseases. However, it is not without its disadvantages. One of them is the lack of precision in estimating the association between multiple exposures and a disease or health outcome. It is also difficult to determine the temporal sequence between the disease and the exposure. The latter is more cost-effective. A case-control study is a useful option for assessing the impact of multiple exposures on a single outcome, such as a cancer risk.